'Wallinar' was one of the earliest farms to be developed in the Broomehill area. The Hardie family moved there in 1905 and began developing their 2468 hectare farm for sheep, cattle and crops, including oats, barley, wheat and canola. Historically the main enterprise has been a Merino sheep stud with animals being provided to properties in the northwest of the state and, more recently, other agricultural areas in the southwest of Western Australia. The Hardies now graze 10,000 sheep and say that they won't be changing that balance. Sheep are the biggest income generators and their high quality 'soft rolling' wool products are now being marketed through 300 stores in Japan.

Two creeks flow through the property with one flowing to the west into the Gordon then the Frankland River and one flowing east also into these rivers but taking a more circuitous route. 'Wallinar' is almost at the top of the Gordon-Frankland catchment.

The Hardies began work to address some of the land degradation and water management problems in the early 1960s and the project has evolved in five stages. The early work was carried out by Mick Hardie (Mervyn's farther) with help from the Cruickshank family, particularly David Cruickshank from Perth. Mervyn and Carol Hardie now have a whole farm plan that they are working to with the aim of eventually achieving an efficiently operated chemical-free farm.

The Problem

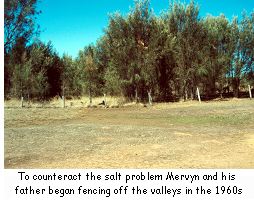

Most of the trees that are growing in the valleys on the farm now were planted in the early 1960s. "Initially the land was cleared in the early 1900s and they over-cleared a lot of the valleys. All the valleys were just cleaned up and stripped out and very few trees were left, they just took the lot. As a result of that clearing, in one generation all the valleys went salty, we finished up in the 1930s and '40s with probably 300 acres of bare salt with nothing growing on it at all. We had a huge salt problem here. I think it's important that people realise that there was a really big salt problem. It was a mess with all the salt seepages. The water table had risen and the water was tested to be saltier than the sea. It was leaching out everywhere and the young stock were doing badly on the salt seepage areas, so we really had to do something".

When Mervyn was a child he recalls that they couldn't move sheep over one of the creek crossings because there was too much water running off the property. Later he remembers that one of the piezometers was just erupting with salt water all the time in both summer and winter.

As well there were erosion problems in the creek from the increased runoff after the land was cleared. In addition many of the areas used to suffer wind erosion every April and May of every year. "The winds used to howl across the paddock and they hit these hills and they completely stripped it out with wind erosion. We were actually losing the topsoil".

The Solution

The Solution

To counteract the salt problem Mervyn and his father began fencing off the valleys in the 1960s. At that time they planted salt tolerant shrubs from the Gascoyne-Murchison area, samphire, paperbarks, 'old man' saltbush, bluebush, paspalum, puccinellia, salt river couch, tamarisk and a lot of casuarinas. During the 1960s and 1970s the casuarinas were planted as seedlings that were taken from the railway line. Mervyn noticed that the yates trees began to regenerate naturally once the stock had been excluded from the creeklines. Later he began erecting electric fences powered by solar panels and planting a combination of habitat trees and agro-forestry trees including salt river gum, river gum, coastal moort, tuart, dwarf sugar gum, bald island marlock, Tasmanian blue gum, radiata pine, tagasaste and wattles.

A program of earth works was also undertaken to fill, level and reshape the eroded areas using a bulldozer or grader. "[We had a] deep salty creek. So I got a bulldozer in and filled it all in to stop the water running down. There was a bad salt seepage, as salty as the sea, overflowing down into the creek. So we just put a two inch pipe down at the bottom of it and it's draining into the creek further down and the trees are just soaking up the water. [This is] a perfect example of reclamation from pure salt to a pasture again, so it can be done".

Some 'shallow plough' type contour banks were constructed to carry away excess water. The existing dams were moved into the hills and compacted soil was loosened using an Austplow during August when the soil was softest.

In 1986 a salinity, hydrology and soil conservation company carried out a geophysical survey of the farm. They found that the groundwater was still rising despite more than 100,000 trees being planted. This was the catalyst that got the Hardies to formulate an integrated whole farm plan with the help of Ron Watkins (Frankland Farmer, winner of numerous awards for achieving a sustainable agricultural system). The plan was put into place in 1989 and included:

- Construction of 11 kilometres of contour banks to control water flow into a system of dams (based on the best principles of the Keyline plan by P.A. Yeomans)

- Planting above the contour banks to provide shelter and control wind erosion

- Agroforestry plantings to help increase cash flow in future years

- Movement towards chemical-free farming that works in tune with the existing biological systems

The dams have been designed as key dams and minor dams and the water overflows from one into the next one and so on. They are all interconnected and there is a four metre fall between the contour banks over the whole property. Mervyn explained the principle behind the construction of one of the dams. "There is a natural saddle in the soil, so by using one of the road excavators we've taken the dirt away and made a bank at the back. That will hold the equivalent of 22,000 cubic metres of water. We're quite high up in the landscape here and there's a pipe and a tap at the bottom of the dam and we will be able to just turn the tap on and the water will gravitate down to the house. It will eventually overflow into the next dam. We did get a bulldozer in to make a deep hole right in the centre, its about 19 feet deep, so there's a lot of water there. Its not used yet for anything but its there because I believe one day the next generation will be able to have nine hectares of something that will support a family. It might be grapes or something as its very fresh water that is being collected".

The dam is a circular shape, "So it is a very cheap way of making a dam. For every one cubic metre of soil removed we obtained five cubic metres of storage capacity. If you make a square dam its one for one, so this is a very expensive way of making them".

After constructing the dam Mervyn put the topsoil back on the bank to allow the grass to grow on it. "We've left that soil there so it's a haven for birds and ducks etc. We purposely left it rough and it will become an island for the native life".

Mervyn explained that originally the grade banks linking the dams were constructed with a bulldozer at $1700/kilometre, and not a grader, which was very important. He now gets a contractor to construct the banks using a backhoe that will do about one kilometre per day.

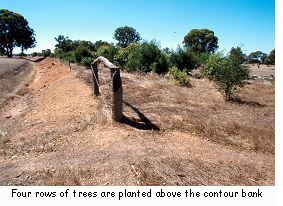

Above the grade banks an area is fenced and four rows of trees and shrubs are planted. The area is deep ripped 12 months prior to tree planting to conserve moisture. "We plant the trees in the deep rip mark so there's plenty of moisture there for them. The key to it in this environment here, because we're 1300 feet above sea level, is that we plant in August. By planting in June we don't get any growth". The fence is constructed using timber from the property and the posts are driven into the ground by a machine and therefore no holes are dug. Three electric wires and two earth wires are used and the fences are constructed to lean into the bank so the stock can't get up and over them. In addition to new fences Mervyn is gradually taking down all the old fences and eventually the whole farm will be farmed on the contour. This will help in water retention as cultivation is done in a herringbone pattern on the contour.

Above the grade banks an area is fenced and four rows of trees and shrubs are planted. The area is deep ripped 12 months prior to tree planting to conserve moisture. "We plant the trees in the deep rip mark so there's plenty of moisture there for them. The key to it in this environment here, because we're 1300 feet above sea level, is that we plant in August. By planting in June we don't get any growth". The fence is constructed using timber from the property and the posts are driven into the ground by a machine and therefore no holes are dug. Three electric wires and two earth wires are used and the fences are constructed to lean into the bank so the stock can't get up and over them. In addition to new fences Mervyn is gradually taking down all the old fences and eventually the whole farm will be farmed on the contour. This will help in water retention as cultivation is done in a herringbone pattern on the contour.

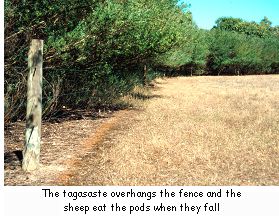

In the early days of revegetation a lot of trees were put on fence lines but since then Mervyn has found that they are much more effective being planted on the contour banks. A method of planting that consists of four rows of trees and shrubs in a 15-18 metre corridor above the contour banks has been found to be successful. Legume shrubs, or tagasaste, are planted on the outside facing the paddock. This allows the pasture to grow right up to the fence and the tagasaste to overhang it and the sheep eat the pods when they fall. Mervyn has found that eucalypts in this position rob the pasture of water and nutrients so that is why tagasaste is planted on the inside. The other side facing the grader bank is planted as a habitat row that includes acacia, bottlebrush, moort, mallee and tea tree. Two rows of eucalypts are planted in the middle and to provide forage for birds and a spring colour display 20% of the eucalypts planted are the brilliant flowering type.

The establishment of the Keyline system of grade banks has enabled an efficient way for driving the stock, they now follow the natural valleys through the property.

The establishment of the Keyline system of grade banks has enabled an efficient way for driving the stock, they now follow the natural valleys through the property.

Dams are still being constructed using natural depressions in the landscape. The idea is to utilise the natural saddles in the soil for the big key dams, therefore working with the environment and not against it. Large amounts of soil don't need to be shifted and Mervyn has found that it is a very effective way of storing a lot of water at low cost. A large key dam (for example 24000 cubic metres) can be put in for a cost of $6000.

The Hardies have purchased more land from their neighbours and have carried the contour banks through that property. They are now working towards completing the work on the entire creekline. They planted trees in August 1999 and they have grown really well. The paddock has been deep ripped ready for cropping in 2000.

The Hardies believe that they should be working to use all the rainfall where it falls and they are using various techniques in addition to the dams to achieve this.

"A year before we crop the paddock we deep rip 30 centimetre on the contour (using an Ausplow machine). We don't turn any soil over; all its doing is just cracking that hardpan that has evolved. It allows the oxygen into the soil and enables the root matter of the plants to nodulate down deep. By getting a lot more root matter in the soil we believe that that will break up over the years into more humus to create an environment for microorganisms and earthworms. This extra humus creates a larger sponge effect underground which in turn has the ability to retain more moisture. Its no good putting microbes into a soil that they won't survive in. The Austplow leaves a corrugated effect under the ground and this helps to hold the rainfall where it falls. When we sow the crop the following year it definitely increases the production and the crop is a lot healthier. [There is] a lot better root structure on the plant and it can nodulate down deep into the moisture. We only do it in July-August when the ground is nice and soft, not when it's dry and too hard and only very slowly so it doesn't pulverise the soil. This is very important".

"We have used deep rooted perennials like phalaris and lucerne, which hopefully will use a lot of water. I think we need a lot more research on these perennials; which are suitable in this environment and those of benefit to the livestock?"

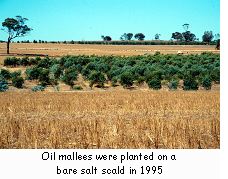

An area of bare salt scald was planted with oil mallees in August 1995. Mervyn decided to go ahead with the trial against the advice of the Department of Conservation and Land Management. "They said that trees for eucalyptus oil would never grow here, it was too salty. I said, 'Lets give it a go we might all learn something'. So they put six different species of oil mallee in and they've done very well. I will be putting in 6000 oil mallees in 2000 in an alley-farming situation so we can graze between. If the oil harvesting comes off then we've got a bit of extra income, if it doesn't well we can use them for carbon credits for the environment". Mervyn believes that the success of the mallees has a lot to do with the fact they the soil was mounded prior to planting. He sees the oil mallees as having an advantage in his farming system because they act as sumps to soak up ground water. They can also be used for products such as reconstituted wood products (panels, fibreboard, cement composites), oils, resins, gums, tannins and charcoal (activated carbon). They can also be used as a renewable energy source by providing liquid fuels (ethanal, methanol) and also solid fuel to generate electricity.

An area of bare salt scald was planted with oil mallees in August 1995. Mervyn decided to go ahead with the trial against the advice of the Department of Conservation and Land Management. "They said that trees for eucalyptus oil would never grow here, it was too salty. I said, 'Lets give it a go we might all learn something'. So they put six different species of oil mallee in and they've done very well. I will be putting in 6000 oil mallees in 2000 in an alley-farming situation so we can graze between. If the oil harvesting comes off then we've got a bit of extra income, if it doesn't well we can use them for carbon credits for the environment". Mervyn believes that the success of the mallees has a lot to do with the fact they the soil was mounded prior to planting. He sees the oil mallees as having an advantage in his farming system because they act as sumps to soak up ground water. They can also be used for products such as reconstituted wood products (panels, fibreboard, cement composites), oils, resins, gums, tannins and charcoal (activated carbon). They can also be used as a renewable energy source by providing liquid fuels (ethanal, methanol) and also solid fuel to generate electricity.

Water is being pumped from an aquifer on the property into a tank for stock water. "In the valley here about 15 years ago we put a magnetometer over it and measured where the bedrock was and where the salt water was, and the aquifers. An aquifer of fresh water was identified so we put a mill on it and it's hooked up to three boreholes". The bore was put in during 1990 and over the last ten years Mervyn has found that it has lowered the water table, and a previously bare valley is now growing grass once again. The water overflows from the tank into the creek and is then used by the trees, so no water is wasted. They have also controlled the surface water coming down from the hill and this has helped in the rehabilitation of the valley.

Mervyn likes to look for alternative ways to manage a problem. Recently Western Power wanted to pull down a group of trees where a power line went through the property. "They had a dozer here ready to go and I knew nothing about it. They said were going to knock all those trees down. I said, 'Wait a minute there must be a better way'. They were very good and they listened. I said, 'Why don't you move one pole and it will move the power line out from the trees'. So they said, 'That's not a bad idea', so they promptly did it. So we saved all those trees through there".

To move from a chemical-free farming system towards a biological system the Hardies are decreasing their reliance on artificial chemical fertilisers and increasing the use of natural minerals. There has been some artificial fertiliser used on the farm and every paddock has been topdressed with dolomite, and gypsum at a very low cost. "We're mineralising the soil, getting the calcium back in, we were very low in calcium on the farm. We use hollow tyres and put natural minerals in there, dolomite, gypsum, lime and salt out of the edge of the lake near Magenta. The sheep come and help themselves to the minerals in the tyres. It's full of all the natural elements that can help feed the soil microorganisms through the dung of the sheep, so it's a chain reaction. This lick also helps to keep the rumen bacteria alive enabling the animals to utilise the poor quality feed in the paddocks. If mankind had tried to put all the cobalt, manganese and magnesium and elements in there in an artificial form they couldn't have done it in a more balanced form. Its got sulphur in it too, you've got to have sulphur to get your amino acids going in the sheep's rumen to grow good wool. By putting it in by artificial means, superphosphate, it has sulphuric acid and it's in a completely unbalanced form. So we believe that after ten or 11 years of this integrated farm plan we will be able to run a third more sheep on it because of the extra feed. That's pretty significant".

The Outcomes and Observations

"What I know now I wish I'd known 30 years ago. We just made a lot of mistakes not doing a whole integrated farm plan. The early `60s reclamation work was from bare and it certainly made inroads into it, but to me we were not controlling the water so it failed in some aspects. Also we didn't have enough balance of trees. These are the mistakes we feel we made and it's important for people to see this and see what can be done when a whole integrated farm plan is set in place. Which is much more exciting because it raises the productivity very quickly because of the shelter effect and controlling the water etc. It used to be fresh water years ago and it went salty, now it's freshening up again. We can turn it around very quickly in my opinion by doing a whole number of things. Ten years can make a huge difference and the whole farm plan has made a huge difference too".

The Hardies have worked hard to implement their whole farm plan and are now enjoying many benefits.

Of the shelterbelts created above the contour banks and pasture improvement using minerals Mervyn says, "This is where I'm really starting to see results. There are 500 wethers running in here now and we give them a bit of straw every two or three weeks off the stubble, straw not hay. That keeps the nitrogen going in the rumen and that keeps them mud fat all through the summer, so its very low cost. It is very sheltered in here too with lots of birdlife. It's also warm in the winter in the sheltered areas and shelter for sheep is important. They don't scour in the winter and don't need as much to eat. I've noticed that the sheep are a lot healthier too and you cut more wool. At the end of the long summer they're still fat and that is very significant as we can sell them for more money because they're in better condition". In 1990 an area of 650 acres carried 1100 sheep and then in 1995 it carried 1400 sheep and Mervyn now believes that without crop it would sustain 1700 sheep.

Of the shelterbelts created above the contour banks and pasture improvement using minerals Mervyn says, "This is where I'm really starting to see results. There are 500 wethers running in here now and we give them a bit of straw every two or three weeks off the stubble, straw not hay. That keeps the nitrogen going in the rumen and that keeps them mud fat all through the summer, so its very low cost. It is very sheltered in here too with lots of birdlife. It's also warm in the winter in the sheltered areas and shelter for sheep is important. They don't scour in the winter and don't need as much to eat. I've noticed that the sheep are a lot healthier too and you cut more wool. At the end of the long summer they're still fat and that is very significant as we can sell them for more money because they're in better condition". In 1990 an area of 650 acres carried 1100 sheep and then in 1995 it carried 1400 sheep and Mervyn now believes that without crop it would sustain 1700 sheep.

"Our wheat crop averaged 4.1 ton/hectare last year and we used to think if we could get a three ton yield a few years ago we were doing well. I'm sure that's a lot to do with the shelter. In the last few years there's been absolutely no wind erosion at all. It's only really in the last two years that I've realised the economic advantages and its very difficult explaining it to people".

"It's very important to have a corridor of vegetation through the property so the little mammals can survive and the predator insects too, so you're getting the balance and the biodiversity back into the ecosystem. One without the other is no good. I think trees are vital and I don't graze any of the fenced off areas. I keep stock out of them to keep the understorey there".

"It's very important to have a corridor of vegetation through the property so the little mammals can survive and the predator insects too, so you're getting the balance and the biodiversity back into the ecosystem. One without the other is no good. I think trees are vital and I don't graze any of the fenced off areas. I keep stock out of them to keep the understorey there".

The creation of the Keyline system of contour banks and dams has had enormous benefits to the farm and also to the creeks running through the property.

"On two occasions we have had a drought and most of the dams have gone dry and we'll never see that again. We hardly get any water running out of this creek now because we're holding that water where it falls. We have a farmer over the hill on this creek that has actually put deep drains in and gone right through the aquifers and dykes and released that water into the same river system. My philosophy is to hold the water up here, to utilise it with trees and perennials, harvest it or use irrigation, whatever. But not to interfere with the natural landscape, which I think is very important. I don't think that we need these deep drains in this environment here. Someone else is getting the problem further down and that's what I don't like. If we can hold the water where it falls it will help reduce the salt effect into our state river systems. Prevention of excess runoff and control of the water are key words in my opinion".

Mervyn encourages others to visit the farm to look first-hand at what has been achieved. He is keen to see others working towards whole farm plans. "Instead of people saying it costs too much money, I can't afford it, in my opinion you can't afford not to do it. It's very important to have a long term goal, aim and objective. It might take you ten or 20 years to just chip away and have a very constructive plan that you're heading towards. And I think its one of the failings of our government agencies and private agencies that they don't have a clear policy backed up with constructive, scientifically evaluated work that is also oriented towards extra income. I feel that once we can start monitoring this we'll be able to prove to people that we're farming in a sustainable manner, especially the consumer".

"I think we need to get our properties back to twenty or twenty-five percent of vegetation to make them economic again, so that's a lot of trees. Trees are also very important for maintaining rainfall. We're probably at about 15%. I've actually had the Agriculture Department put this on computer so we can measure it. There's about 650 acres of trees here on 5000 acres".

"I'm just realising how little we know about our own country and the potential for production and I'm only just scratching the surface. Once I start utilising this water they tell me that you only need nine ha to support a family if its done properly using permaculture. It's just set up for the next generation really".

"I feel it's important to mention these points so that the next generation can move on and improve what our generation has learnt. To quote Ron Watkins "We need to work with the environment not against it'".

"To quote a proverb which has had a big influence on me:

Nothing in the world can take the place of persistence

Talent will not - nothing is more common than unsuccessful people with talent

Genius will not - genius unrewarded is almost a proverb

Education will not - the world is full of educated derelicts

Persistence and Determination alone are omnipotent"