The Beaumont area, which is about 90 kilometres northeast of Esperance, was opened up for farm development in the early 1970s. Ted Young moved to his farm in Beaumont Road in 1975 and put in the first crop after the previous owner had cleared and ploughed it. Ted has concentrated on crops such as wheat, barley, canola, lupins and field peas since the fall in wool prices but hopes that sheep will improve so he can cut back the cropping program.

The topography of the area is unique in that there are numerous small lakes and wetlands and very few natural drainage lines. The average rainfall is officially 440 millimetres. but Ted has experienced extremes of 750 mm. down to about 300 mm. During 1998 and 1999 the property received over 500 mm. of rainfall during both years.

Ted has been working to improve the drainage of the property and has used a combination of grade banks, scraper drains, grassed waterways and tree planting to control excess water over the whole property. This method of control moves the water from the paddocks to the wetlands and then trees are planted to use the water from the wetlands.

The Problem

The Problem

Ted has noticed that the front of the farm is different to the back half in terms of soil types and salt encroachment and has experienced different problems because of this. "The track goes the length of two blocks and basically divides what I consider the sand plain country at the back (although the vegetation is mallee it has got a lot of salt lakes in it) and the front half, which is more mallee country with not much salt in it. All our non-wetting sand problems are on the back half of the property, the sand country, and that goes with the ponding. The lower profiles seem to be where the clay soils are and the higher land tends to be non-wetting sands".

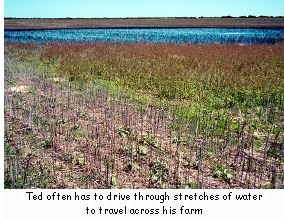

Ponding or waterlogging has been a big problem, especially during the wet years of 1989, 1992 and 1995. At times water has been lying around in areas up to 150 metres wide and 300 metres long, and Ted often has to drive through stretches of water to travel across the farm. "You only need a small catchment for a puddle in this type of country. When we had big stock numbers the depressions were ponding in the wintertime and then drying out over the summer. The sheep used to camp on them and they'd blow out and they've got quite big banks of sand around them now".

Ted began 'landcare' work 1981. "We didn't call it landcare in those days, it was more farm beautification, planting trees on fencelines and things. It wasn't until the mid-80s that we started to realise that this ponding was going to become a problem. We'd been talking about it almost every day since we'd been here but we never really had any solutions. Particularly with cultivation it was a lot worse. In wet years with more tradition cultivation methods everything used to get that waterlogged our crop would be virtually non-existent. In the cropping year of 1995 all the low-lying areas got badly waterlogged. We did some sums and we'd lost 80 acres out of 800, 10% of the land was waterlogged to some extent. We got 2.5 ton of wheat on a lot of it and in the ponding patches we had nothing and out on the edges we had 30-40% losses".

The Solution

The Solution

In the areas subject to ponding Ted put in some low-level drains using a scraper in February 1999. A laser level was used to survey the position for the drains and initially he didn't get it quite right because there were still a few 'puddles' in the actual drain itself. "We took all the topsoil off with a clay grader and stockpiled it and then we made a wide spoon drain". The ten foot clay grader carries its own ripper and is pulled with a four-wheel drive tractor and can carry about 14 tons of clay. The amount of soil moved was from 1.5-2 metres deep, depending on the fall of the land.

Most of the clay out of the scraper drains was spread on the non-wetting sands. "With the non-wetting soils it actually compounds the problem because when we get heavy rainfall events none of the rains soaks in, it just runs straight off. So if you get a thunderstorm and get 1.5 inches, when it stops raining the top inch of the non-wetting soils will be wet but it will be dry down another foot. All the water that fell on it runs into the ponds. So the clay that we're putting on the non-wetting sands will hopefully make it absorb much more of the rainfall. So we should have less runoff and what runoff we do get we will try and get off the paddocks as quickly as possible".

The idea of 'claying' has only been popular in the area for the last two years and prior to that Ted was using an ordinary scraper to construct the drains and didn't know what to do with the spoil. "We were putting it around all the low lying areas, around the edges of them. Because it's pure clay it turned out to be a bit of a problem because the clay doesn't disperse very well and it is sitting on top of all the topsoil. When we saw what was happening we realised that all that clay out of those drains should have been used for mixing in with the non-wetting sands. So that was the idea behind buying a clay grader and it's ideal for doing this sort of work".

The idea of 'claying' has only been popular in the area for the last two years and prior to that Ted was using an ordinary scraper to construct the drains and didn't know what to do with the spoil. "We were putting it around all the low lying areas, around the edges of them. Because it's pure clay it turned out to be a bit of a problem because the clay doesn't disperse very well and it is sitting on top of all the topsoil. When we saw what was happening we realised that all that clay out of those drains should have been used for mixing in with the non-wetting sands. So that was the idea behind buying a clay grader and it's ideal for doing this sort of work".

"The idea with theses drains too was to make them so that we could crop through them, so that they wouldn't erode too badly and they would always have something growing in them". What we do is we take all the topsoil off and stockpile it next to them. We usually take off the first 12 inches, depending on how far it is to the clay, and then once we get to the clay we use the clay on the non-wetting sands. When we get the drain down to the right depth, we usually go a bit deeper than we need to, then we come back and put whatever topsoil we've got back in the drains. So we mix the soil in the spoon drains so you can crop right through them and hopefully it's the same as the paddock. There is as much topsoil in the drain as there is on the soil that hasn't been touched. In effect it probably doesn't work quite that well but this year the crop wasn't a lot different in the drain to what it was in the rest of the paddock".

Ted believes that there won't be a problem with the drains silting up. "The idea is that they don't run very quickly anyway. It's probably only a half a metre fall from the road to here so they don't run at any great speed and we wouldn't expect that it's going to shift much topsoil the way they run. So no, we don't expect them to silt up, but if they did, with this machine (clay grader) we can shift a lot of soil in a very quick time".

In 1997 Ted hired a contractor to construct a drain using a traditional scraper and didn't use the soil to put on the non-wetting sands. It was basically a scraper drain that divided a paddock into two sections and it couldn't be cropped through. The aim of the drain was just to link up several low-lying areas, some of which used to fill up with water to the size of a football oval. Ted found that this drain worked really well and within half a day of rain falling on the low-lying areas they were virtually dry. He also found that at $3000 for the scraper it was a cost-effective exercise.

In 1997 Ted hired a contractor to construct a drain using a traditional scraper and didn't use the soil to put on the non-wetting sands. It was basically a scraper drain that divided a paddock into two sections and it couldn't be cropped through. The aim of the drain was just to link up several low-lying areas, some of which used to fill up with water to the size of a football oval. Ted found that this drain worked really well and within half a day of rain falling on the low-lying areas they were virtually dry. He also found that at $3000 for the scraper it was a cost-effective exercise.

The drains all eventually empty into one of the numerous natural lakes on the property and Ted has been fencing them and planting trees to use up some of the excess water. The area is ripped prior to planting six to eight rows of trees. Generally local species are used such as yate, paperbark, and mallee species although Ted has also planted some sugar gum. "Generally we like to rip the year before but sometimes it just doesn't happen because of various farm activities. With all the rain that we've just had this year it's a perfect opportunity for us. So we're actually [weed] spraying in the morning and ripping tree lines in the afternoon and we've got about 25 kilometres of tree lines to do". The ripping is done a year in advance, mainly to allow the holes to collapse back down again. Generally what we do is rip the lines then drive around with a tractor wheel on them to try and compact them down again. If you don't do that, when you plant the trees, quite often the roots will end up in air cavities and they'll die. So if you leave them ripped for a year not only does it collect a lot of moisture but the holes collapse back down again and there are no air pockets in there". Ted does the tree planting in July or August and goes from seeding crops to planting trees. Sometimes if the soil is too wet he waits for it to dry out to minimise the effect of waterlogging on the young trees.

The trees that were planted as seedlings in 1993 have had a mixed success. "We did plant bottlebrushes and pin cushion hakeas but the bottlebrushes won't stand up to the competition in normal bush settings, well not in this rainfall anyway. The yates, sugar gums and wattles are doing OK. The Casuarina obesa, they are tough and they started to grow three years after we planted them. In 1993 it was a dry year and I worried about them surviving, but they did". Some self-sown wattles have started to grow in some of the fenced areas.

The trees that were planted as seedlings in 1993 have had a mixed success. "We did plant bottlebrushes and pin cushion hakeas but the bottlebrushes won't stand up to the competition in normal bush settings, well not in this rainfall anyway. The yates, sugar gums and wattles are doing OK. The Casuarina obesa, they are tough and they started to grow three years after we planted them. In 1993 it was a dry year and I worried about them surviving, but they did". Some self-sown wattles have started to grow in some of the fenced areas.

Some of the depressions in the front part of the farm have gone salty and eventually Ted hopes to have them all fenced off and to have trees or saltbush planted around them. He first planted saltbush five years ago on a very bad salt scald of about 12 hectares. The area was mounded first but no ripping or weed control was carried out. He got a 95% survival rate and was very pleased with this result.

He wants to try and save some of the depressions that are not yet salty and is trying to plant around those first. "We don't want to lose those to salt so the idea is to get the water off as quickly as we can. It seems that some were always going to go salty and that some are never going to go salty. It's a strange situation here, they don't look any different across the farm but some are going out to salt. Down the other end of the farm the water table must be higher and we've lost six or seven of these depressions. We are planting saltbush in the ones that aren't too badly affected but a lot of the saltbush areas are now under water. In the past we haven't had too much summer rain so the saltbush has been able to suck quite a bit of water from directly below them so that when we do get rain it hasn't ponded. But because they are only such small plants and they're not properly established yet they haven't had time to dry the area out enough and now they're under water". Ted successfully grazed some of the saltbush areas during 1999.

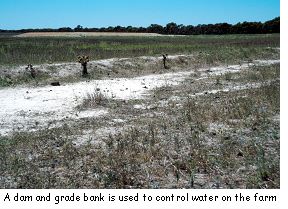

In 1988 Ted started using grade banks as another method to control the water on his farm. There used to be a lot of runoff from the areas of heavy clay soils that used to flood down into the lower areas and cause waterlogging. A new dam was built and the grade banks were constructed to run into the dam. Ted has found that the banks have made a huge difference to his cropping success. "During the cropping last year we didn't have a wet year, but in a normal situation we would have had quite a bit of crop loss down there. It has stopped the water running off the slope. It doesn't look much of a slope but it really does get quite bad in that low-lying area".

In 1988 Ted started using grade banks as another method to control the water on his farm. There used to be a lot of runoff from the areas of heavy clay soils that used to flood down into the lower areas and cause waterlogging. A new dam was built and the grade banks were constructed to run into the dam. Ted has found that the banks have made a huge difference to his cropping success. "During the cropping last year we didn't have a wet year, but in a normal situation we would have had quite a bit of crop loss down there. It has stopped the water running off the slope. It doesn't look much of a slope but it really does get quite bad in that low-lying area".

"We didn't have a dam in this paddock so we though it was an ideal opportunity to use the water that we were catching off the paddock for stock water, so we combined the two. The dam was done with the farm water supply grants and we were able to get 25% of the cost of the dam.

We put the grade banks in ourselves with our own grader. They were done in autumn of '98, so they were in before last year's big rainfall event and they handled this year's rainfall event OK. So they've had two summer rainfall events on them and they've withstood that no problems at all, so I think they've done a good enough job". Ted will eventually plant trees along the lower side of the grade banks.

In 1998 in between the grade banks Ted put in a grassed waterway or spillway. "The idea of the spillway is that it's supposed to be slightly lower than the banks everywhere else but still level. So when it fills up it is supposed to flow over the whole width of the spillway rather than just cut a trench. So the water is contained in this spillway and it runs down and around into the creekline. Every now and then there's a little cutting [in the grade bank] so that any water that's caught on the outside of the spillway can actually run in. This hasn't been cropped since the grade banks were put in and we won't spray it either. With grassed waterways the idea is not to tree them because the trees restrict grass cover and then you get erosion. The water runs about half an inch deep along the waterway and it's never a torrent. It the only way you can get water from the top of the hill to the bottom of the hill without erosion. It seems like you're losing a lot of country but you're not really".

The Outcomes and Observations

The Outcomes and Observations

"Since we've been minimum tilling we don't have anywhere near as much waterlogging and combined with the drainage and all that sort of thing we reckon eventually, in about another three or four years, we'll have the property almost flood-proof. It will still affect our yields in very wet years but it won't write us off like it used to".

Ted has noticed that where trees and saltbush have been planted in the depressions that had become salty the spread of salt has been arrested. He attributes this to the plants helping to dry out the soil and has noticed that now even with a lot of rain the water doesn't lie around in the depressions. "When we did this it was farmer driven and a lot of the experts were saying that the trees should be up on top of the hills not down in the valley". The landholders decided to plant in the valleys as an experiment and Ted seems to think that it has worked quite well so far. He is not sure, however, whether the trees and saltbush are enough to stop the water table rising in all parts of his farm.

The amount of regrowth of paperbarks and other riparian vegetation around the wetlands since the sheep have been removed has been quite remarkable. Some of these have not been fenced as Ted says, "For me to fence everything off on this farm would cost a fortune". He is working towards fencing some of the areas that have shown a high level of natural regeneration after the 1999 flood.

Of the drainage works Ted believes that the main work is getting the levels right. "After the ponding we took some levels and realised that we only had to remove about a metre of soil over about 50 metres and we could drain it. So that became the basis for doing what we did and it's worked well. It's a bit hard to know what to do with the isolated ones as there's no [natural drainage] system. In some it was obvious that they all linked up and when we took all the levels each one was slightly deeper than the other so we took advantage of the natural fall".

Ted has now linked up several low-lying areas with drains, which has decreased crop losses and he believes that they have done a marvellous job. However, he does see a disadvantage in putting in grade banks and says, "The only thing wrong with grade banks is if you follow the letter of the law by making sure you stick to your grades you end up with a fairly untidy line. Then it wanders around all over the place and it makes it a little bit difficult for cropping".

Ted believes that some of the lakes could take a lot more water but he hasn't worked out how to get it in there without having to construct drains all over the farm. In total Ted has installed 2 kilometres of spoon drains with the clay grader, 1.5 kilometres of scraper drains and four to five kilometres of grade banks and he has at least twice as much to do in the future. He is looking at draining more of the depressions and claying on more of the non-wetting sands.

With the revegetation work Ted says, "I think in hindsight we might have come another three or four rows of trees out, but it was a bit of a learning curve, we weren't really sure what we were doing. I didn't want to give any more land than I had to. I think that we've all probably learnt that an extra chain either side really doesn't matter much".

A project is underway at present to install 40 piezometers across the area to compliment the data being collected from a demonstration piezometer site on the farm. Ted believes that this will give the farmers in the area a better idea of what the water table is doing. "The ones in the demonstration site haven't told us anything, nothing has changed in the seven or eight years since they've been there. The three at the top of the hill are about the same distance from the creekline and they've been dry the whole time. The ones down the bottom of the hill vary from about a metre to about a metre and three quarters just depending on when you do them. They're not really telling us anything; all they're telling us is that nothing is changing. Some people say if we don't do something were going to lose a lot of this country, but I don't think we really know yet whether this sort of work [tree planting] will help a lot".