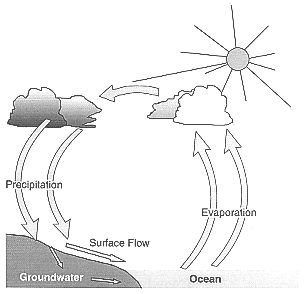

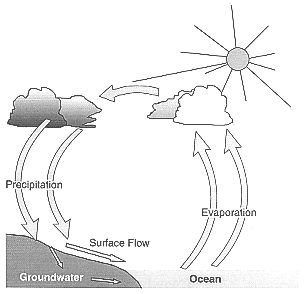

Figure 5-1: The hydrologic cycle

Water movement

The hydrologic cycle is a never-ending circulation of water throughout the environment. Water is evaporated from the ocean by the sun. It turns into water vapour and clouds and is blown over the land by the winds. When geographical and weather conditions are right, rain, hail or snow falls onto the land. This is known as 'precipitation'.

Some of this precipitation that falls on the land:

Figure 5-1: The hydrologic cycle

After the rain, hail or snow, the water continues through the hydrologic cycle along a number of different paths. Most of the water will go back to the atmosphere in evaporation and transpiration, some will seep through the soil and become part of the groundwater, and the rest will become surface water flow (known as `runoff').

Run off is the most important part of the hydrologic cycle for shaping landforms, even though only 0.0001% of all water (and 0.004% of fresh water) is found in rivers at any one time.

| Runoff = precipitation - (infiltration + evaporation + transpiration) |

The circulation of water through the hydrologic cycle is relatively rapid, except where the water is moving underground. There it may take hundreds, or even thousands, of years to return to the sea.

Groundwater is held in the spaces between grains of sand and pebbles, or in rock fractures and cracks. Rainfall filters through the soil into the groundwater over most of the coastal plain. Not all of it gets through to the groundwater because vegetation acts like a pump, taking up water from the soil and from below the watertable. Only about 19% of rainfall actually enters the groundwater system. The rest is taken up by plants or evaporated by the sun.

In the Perth region the watertable forms a broad mound. It is called a 'mound' because it looks like a mound if it's viewed in cross-section. At its peak it's 70 metres above sea level. The groundwater flows outward from the central point to the ocean and rivers. It's called the Gnangara Mound, and is just to the north of Perth. It is the most important source of high-quality groundwater in the metropolitan area. Immediately south of Perth there's a much smaller groundwater reservoir called the Jandakot Mound. At places other than those two mounds, the groundwater doesn't collect as dramatically, but flows generally westward to the sea or rivers.

The groundwater moves horizontally at rates of 50-100 metres per year. How fast it moves depends on how easy it is for the groundwater to move through the sand (known as the sand's 'permeability') and how steeply the watertable slopes.

Groundwater usually flows into streams, the sea or estuaries, but occasionally flows out as springs. Wetlands form in low-lying areas where the watertable meets the ground surface, or at inland discharge areas where the ground's surface is lower than the watertable. In most coastal areas fresh groundwater overlies a wedge of salt water which gradually tapers inland. The position and depth of the wedge varies from place to place, depending on the height of the watertable above sea level and the amount of groundwater flow. If the flow of groundwater decreases because there have been a few years without much rain, or because a lot of water has been pumped out through bores or wells, then the saltwater wedge may move further inland. This may mean that bore water becomes more salty. If the wedge is big and close to the surface, it can affect the plants that `pump' the salty water into their roots and leaves. This can kill them.

Groundwater is polluted if its quality is degraded by humans so that it's no longer able to provide water the way it once could (such as for plants to use, or for humans to drink). There is such a large amount of water in the coastal plain groundwater that massive pollution is unlikely to happen. Most groundwater pollution problems tend to be localised events. For example, the CSBP site at Bassendean and Bayswater has been contaminated with high nutrient levels which have leached into the groundwater, creating a plume of contaminated water moving towards the river. Once groundwater has been polluted it's almost impossible to remove it. It can take decades or even hundreds of years for the pollution to be removed by flushing out, by being diluted by more water, or by being dispersed harmlessly over a wide area.

Pollution may be removed by pumping out the polluted groundwater but this may be expensive. Even localised groundwater pollution must be treated seriously. The cumulative effect of many minor pollution incidents could create a serious problem.

There are many potential pollutants - such as from septic tanks, leachate from landfill, petroleum products and industrial wastes - and numerous ways that they can reach the groundwater.

Septic tanks can be a problem in densely populated urban areas because nutrients from them seep into the groundwater and build up over time. These nutrients can be helpful where the groundwater is used to irrigate crops and gardens, but if they get into lakes, drains and rivers they can help algae grow and cause major problems.

The pollution of groundwater is caused by people. Preventing groundwater pollution depends on good planning about how land is used and then managing people's use of the land and water. It's most important that potentially polluting activities are put in places where dangerous pollution can be controlled. It's also important to collect rubbish and other wastes from houses and industry carefully, and dispose of it at places that are going to harm the groundwater the least, and are run efficiently and carefully.