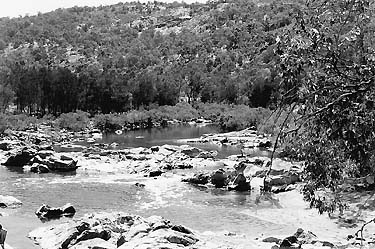

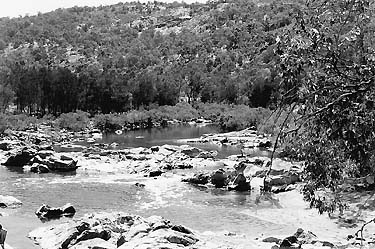

Bells Rapids, Avon River

Ecosystems

Bells Rapids, Avon River

|

An ecosystem is all of the interactions between plants, animals, soil, water, fire and air in a specific environment.

A river or an estuary is an example of an ecosystem. |

Within an ecosystem, matter and energy are taken up by primary producer organisms (such as trees and other green plants) from their surroundings and passed from organism to organism through the food web. Matter is progressively used by each organism and returned to the air, soil or water. Energy is also lost from each organism and dissipated as heat. For example, an animal is eaten by another animal. Some of the energy from the eaten animal is used by the second animal, and some is turned into waste, such as heat and droppings.

Ecosystems get nutrients, minerals and gases from the weathering of rock, the atmosphere, other ecosystems and the decomposition of organic matter. Ecosystems get energy from the sun. A lot of these inputs are recycled through the ecosystem: when larger creatures eat plants or when leaves rot through the work of bacteria, for example. Ecosystems have outputs, too. They release heat energy to the atmosphere, and nutrients and organic matter to other ecosystems.

| For more information about food webs and energy transfer see section 2.3 - Food webs |

Riverine ecosystems are generally less complex in nature than estuarine ecosystems as they are not influenced by the marine environment. These ecosystems vary from a narrow creek which runs only in winter to the lower reaches of a river which drains a large area of land. Riverine ecosystems of south-western Western Australia can be divided into three distinct zones:

A typical channel is often no more than a few metres across, while a riffle can be 5-20 m across. A riffle zone may consist of shallow water passing over stones, forming rapids, while in other areas it can be densely vegetated, with shallow water passing between clumps of sedges and tree trunks.

Deep pools are found dotted along the length of a river where the water speed slows and deposition occurs. In south-western Western Australia, these pools can be 50-500 m long, are typically 20-50 m across and 3-9 m deep.

The ecosystems of river channels are important because they connect and replenish the pool ecosytems. The riffle ecosystems dry out in summer and fill up in winter, so they are not as diverse as the other two types. However, these zones are an important replenisher of oxygen to the river system. The water is aerated as it passes over the riffle's rocks.

Aquatic communities are quite different in the three riverine zones because of each zone's distinct physical characteristics. The communities of the pools and channels are generally similar to those of lakes, ponds and, often, estuarine ecosystems. However, the communities that exist in the riffles are more specialised species adapted to the harsh conditions. During the summer months, when the channels and riffle zones dry up, the pools remain, providing sanctuary to many aquatic animals, including birds, turtles, water rats, fish, crayfish, shrimp and mussels.

Riverine ecosystems are greatly influenced by their adjacent land environment. A large proportion of the energy within the ecosystem comes from the organic vegetable matter from nearby land. For example, leaves from trees and aquatic plants can provide important food sources for many fish. Clearing vegetation along rivers for agricultural purposes has altered this energy flow.

| An estuary is an enclosed body of water which has an open, or intermittently open, connection to marine waters. Water levels vary periodically as the tides rise and fall. |

An estuary's salinity (the saltiness of the water) changes depending on how the sea water mixes with the fresh water from the rivers and streams which drain the land.

Estuarine ecosystems are an important contact zone between freshwater and marine environments. These ecosystems are complex and fertile. They get nutrients from:

These ecosystems are amongst the most naturally fertile in the world.

Estuaries provide a combination of shelter; a good food supply; sheltered waters; protection from predators, competitors and even parasites; and a variety of physical habitats, attracting a wide range of plants, insects and animal species. Fish use estuaries as spawning, feeding and nursery areas, while millions of waterbirds gather on estuaries to feed on abundant food supplies and roost in the fringing vegetation.

The precise form and productivity of an estuarine ecosystem varies according to the local geology, geomorphology, climate and hydrology. In sheltered estuaries the rates of sedimentation (sand deposition) may be high. Estuaries may be completely or partially open to the sea with sandbars, sand spits or sand dunes blocking their entrance.

Estuaries have sudden and often extensive physical changes of salinity and temperature. Plants and animals must adapt to cope with these changing conditions. But estuaries are also rich in nutrients compared with the rivers and oceans. If a plant or animal species can adapt to living under such conditions they are often very successful, occurring in large numbers over a wide area of the estuary. Although not all estuaries are the same, it is reasonable to say that living in an estuary is a strong challenge for its plants and animals and any intruders which might venture into it from the sea or the river.

Many estuarine organisms have probably been forced out of the more physically stable conditions in the ocean or fresh waters at some stage during their evolution. The estuary, having less than perfect physical conditions, was not their preferred home. It did, however, protect them from predators, competitors and parasites. Over time these organisms have developed strategies, either physical, biological or chemical, in order to live and survive in the estuary.

Salinity

| More information about stratification is available in section 4.4 - Parameter 1: Salinity |

Stratification usually occurs in the winter months, or after summer cyclones when run off increases the amount of fresh water entering the estuary. Stratification can help organisms and other materials move in and out of the estuary. However, it may also result in the deoxygenation (fresh water contains more oxygen) of bottom waters, which can cause problems for creatures and plants.

Temperature

Not only must biota (all plant and animal life within an ecosystem) be able to survive or escape large salinity changes, they must also be able to tolerate large changes in temperature and light intensity. The temperature of a waterbody can be affected by any discharge of water or wastewater, such as the discharge of cold bottom waters from dams. Temperatures may get too cold for algae to grow in winter. In addition, large changes in the temperature of a waterbody can disrupt the breeding cycle of some organisms, such as fish.

When stratification occurs, the temperature of the deeper water may be either lower than at the surface (owing to the sun warming the surface of the water) or higher (because sun-warmed water is later trapped beneath wind-cooled surface waters).

Nutrients (chemical compounds that assist the growth of living things) in waterway ecosystems are important because they are vital to plant and animal life. Estuarine ecosystems can store high levels of nutrients. Pristine estuarine ecosystems have most of their nutrients tied up in the plant biomass, usually in seagrasses and tidal marsh vegetation. These plants provide an important food source for grazing fish and waterbirds. This nutrient storage capacity makes the estuarine ecosystem one of the most productive ecosystems in the world. Excessive quantities of plant nutrients (usually nitrogen and phosphorus) can enter an estuarine ecosystem as a result of human activities (such as fertilising paddocks and lawns) and disrupt the natural functions of the ecosystem. This condition (known as eutrophication) can often be recognised by increased amounts of algae and other aquatic plants.

Water circulation in an estuary is generated by the tide; the wind; the flow of water from rivers; and the size and shape of the estuary and its opening to the sea. Typically, the water in an estuary which has a small entrance, low run off from the surrounding catchment and a large surface area may circulate less than a small estuary with a large entrance and high run off. Water circulation helps waters to mix within a semi-enclosed water body. This water movement transports nutrients and plankton, removes plant and animal wastes, controls salinity and shifts sediments. How much the water circulates depends a lot on the tides and the wind.

The exchange of water (known as flushing) between an estuary and sea is also important. The flushing rate (how fast the water flushes) determines how quickly pollutants and nutrients will be removed from the ecosystem. Many animals and plants are also dependent on tidal flow and flushing to help them move between estuarine and marine environments. Estuaries with poor flushing generally have more problems from pollutants and nutrients from the surrounding land than estuaries with high flushing rates.

Sheltered areas within an estuarine ecosystem provide important quiet and protected places which creatures use for breeding and feeding. Many marine creatures enter estuaries to use these areas, as such places don't exist in the open ocean.

In the shallow parts of an estuary, light penetrates to plants on the bottom and fosters the growth of important aquatic life. These shallows are safe places because they aren't visited by many marine predators.