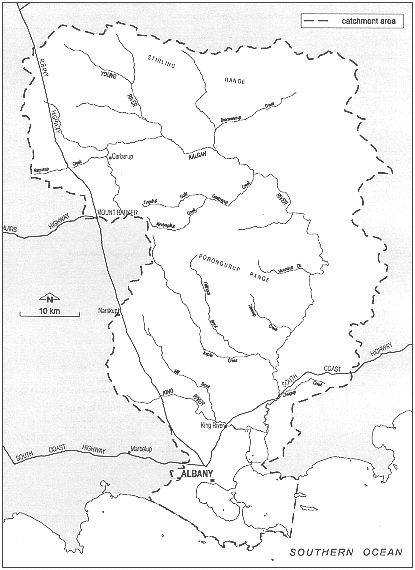

Figure 3-1: Map of the Albany harbours catchments

The catchment area

Figure 3-1: Map of the Albany harbours catchments

The Albany harbour catchment area is made up of two main catchments: Oyster Harbour (total area 304,092 hectares) and Princess Royal Harbour (total area 8,351 hectares).

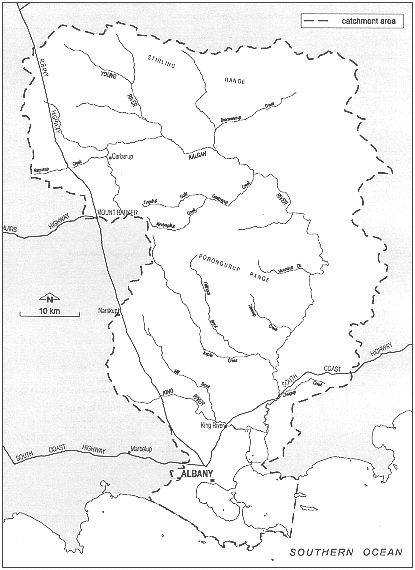

Oyster Harbour's large catchment extends to the south of the Stirling Range and includes a big area of internal drainage east of the Kalgan River. Subcatchments of the Oyster Harbour catchment include King, Mill Brook, Upper Kalgan, Lower Kalgan, North Oyster, Chelguip, Willyung, Johnston Creek, Yakamia and the Town of Albany. The greater southern part of the Oyster Harbour catchment is in the Shire of Albany. However, the Kalgan River catchment extends north into the Shires of Plantagenet and Cranbrook. Mill Brook, a main tributary of the King River, extends into the Shire of Plantagenet.

The Princess Royal Harbour catchment is very different. Limeburners Creek is the only natural stream flowing into it. Other watercourses have been converted into agricultural and urban drains. These also drain low-lying areas around the harbour. Robinson and Munster Hill drains, located to the north-west of the harbour, are the main sources of 'fresh' water flow.

| Town | Average Max. Temperatures (°C) | Average Min. Temperatures (°C) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summer | Winter | Summer | Winter | |

| Albany | 22.9 | 16.2 | 15.8 | 9.0 |

| Mount Barker | 26.1 | 15.3 | 13.1 | 6.6 |

From the table above, it's easy to see that inland areas have the greatest temperature range.

| Catchment section | Average annual rainfall (mm.) | Average annual evaporation (mm.) |

|---|---|---|

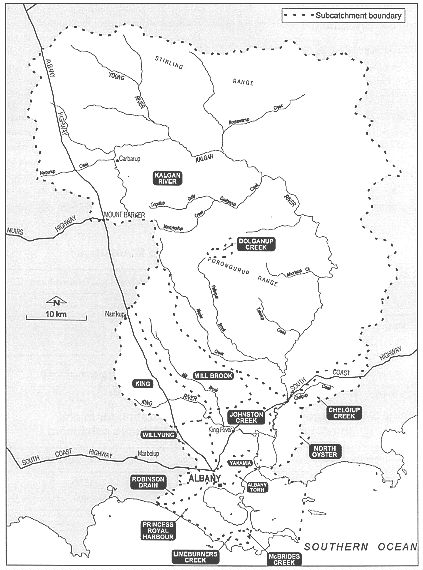

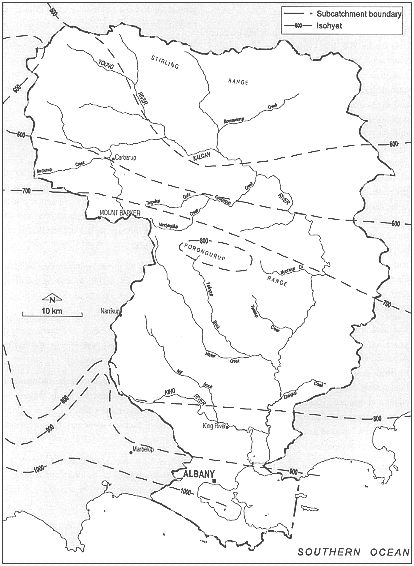

| Inland | 400-800 | 1400-1500 |

| Coast | 900-1100 | 1200-1400 |

Rainfall and evaporation varies markedly between the coast and inland.

| Town | Annual Mean Humidity at 9 a.m. | Annual Mean Humidity at 3 p.m. |

|---|---|---|

| Albany | 73% | 62% |

| Mount Barker | 73% | 59% |

Humidity is consistent throughout the catchment.

The dominant winter winds, associated with fast-moving depressions, come from the west. The strongest winds are experienced on the coast. The dominant summer winds are caused by high pressure systems and come from the east. These tend to be south to south-easterly sea breezes.

Figure 3-2: Albany harbours subcatchments

The climate of the catchment is influenced by a weather pattern known as `the sub-polar pressure belt'. This belt brings high and low pressure systems, and polar cyclonic fronts. These systems and fronts move eastwards across the whole southern portion of Australia. In winter, the pressure belt moves towards the equator, and in summer it moves towards the South Pole.

Figure 3-3: The Albany region showing rainfall isohyets (mm)

The climate is warm and temperate with wet winters and dry summers. Rain-bearing cold fronts sweep inland and from west to east, gradually decreasing in potency as they go.

On average, the hottest month is January. The coldest month inland is July; and August, on the coast.

The area was relatively stable for 900 million years until Australia started to separate from Antarctica in the Early Cretaceous about 120 million years ago. The pulling apart of the landmasses caused `sagging' at the continental edges and resulted in the formation of the Bremer Basin to the south. Depressions and drainage courses developed as a result of the tilting of the landscape accompanied by active erosion.

During the Eocene (about 50 million years ago), the Bremer Basin was developing with these depressions being infilled with river and swamp deposits, now known as the Werillup Formation. In the Late Eocene (about 40 million years ago), with higher sea levels, the Werillup Formation was further covered by fine-grained marine sediments and spongolite (sponge spicules) deposited throughout the area when the shallow sea extended inland as far as the present-day Stirling Range.

After the sea had retreated (about 30 million years ago) to a level similar to that at present, there was another southward downward tilting of the landscape in a tectonic event called the Jarrahwood Axis. This tilting resulted in the formation of the modern drainage features, such as the Hay and King rivers, which cut down through and eroded the Eocene sedimentary and Proterozoic rocks.

In the last 30 million years, there has been active wind and water erosion of the landscape resulting in the formation of weathered deposits from the gneissic rocks, alluvial deposits in the modern streams and creeks, and coastal limestones forming prominent dunes near Albany.

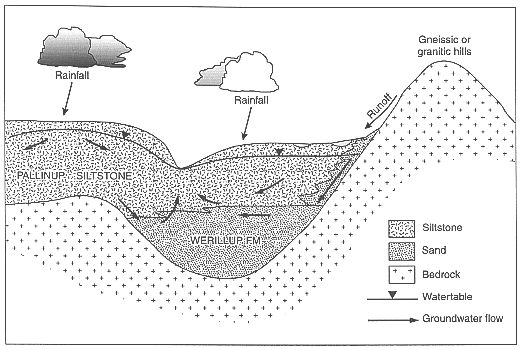

Groundwater or underground water is water that occupies the openings, cavities and spaces in the rocks. It is important to study and understand the geology of an area to understand how and why groundwater occurs in the different rock and sediment types.

The source of all groundwater in the catchment is the infiltration of rainfall. Where the soil profile is sandy, more water soaks in.

A regional watertable forms an almost continuous surface throughout the catchment representing the level below which all pore spaces and cavities within the rocks are saturated.

Figure 3-4: Geology of the Albany region

The watertable usually follows the outlines of the topography but in a toned down way. (Figure 3-4, above) The watertable is usually deepest below hills and high parts of the catchment and shallowest in the valley floors.

Water moves under the influence of gravity from higher to lower parts of the landscape. The higher the gradient and the more permeable the material, the faster the water moves.

The landscape in this area is fairly flat and most of the rocks and their weathered products have low permeability and transmit water slowly. As a result, water moves very slowly (less than 1 m/year) regionally towards the south and locally from higher elevations before discharging into the rivers and sea.

Rain and wind carry traces of sea salt and deposit it inland. The amount of salt deposited in rain and dust decreases with distance from the sea. Over a long period, a lot of salt has accumulated in the subsoils. The amount of stored salt is least in the high rainfall areas which have generally moderate relief and good drainage and most in low rainfall areas where the relief is low and the drainage system poorly developed.

Locally, groundwater is generally freshest beneath catchment divides and high in the topography. Groundwater tends to become more saline as it moves down-gradient towards rivers and salt lakes. The regional salinity of groundwater gradually increases towards the north reflecting the decrease in rainfall.

Stock-quality groundwater is available throughout the catchment but large quantities of good quality groundwater, suitable for human consumption, are restricted to the limestone dunes south-west of Albany where the rainfall is high and the limestone permeable. Small fresh groundwater supplies may occur near outcrops where runoff from exposed bedrock increases local recharge.

The clearing of native vegetation and replacement by annual crops and pastures has led to an imbalance in the groundwater system throughout the catchment. The shallow-rooted crops and pastures use less of the infiltrating rainfall than the deep-rooted native species. The increased recharge cannot be balanced by increased discharge because the landscape materials have low permeability and the landscape is too flat. There is an increased storage of groundwater resulting in rising watertable levels, in the order of 0.1 to 0.3 m/year. Groundwater levels are rising most rapidly in areas with high rainfall and inadequate drainage.

Salinisation is a widespread problem in the south-west of Western Australia and is particularly severe on the southern coast. Most instances of rising watertables and salinisation in the catchment are related to poor development of surface drainages (rivers and creeks) and the inability of the Eocene sediments (Pallinup Siltstone) to transmit much groundwater. Consequently, groundwater and salt cannot be flushed out of the system resulting in rising watertables, accumulation of salts and development of salt scalds on the surface.

Figure 3-5: Diagrammatic section to show groundwater flow

Adapted from Figure 6, R. A. Smith, Hydrogeology of the Mt Barker-Albany 1:250 000 Sheet, Hydrogeological Map Explanatory Notes Series, No. HM 1, Water and Rivers Commission, Perth, 1997, p. 12.

The soils of the northern part of the catchment, lying between the Porongurup and Stirling ranges, are duplex soils. These kinds of soils are called `duplex' because they're made up of two different soil textures. In Albany's case, a sandy top and a yellowy clay lower part make up the `duplex'. The lower part in particular tends to be alkaline.

They are also what's called `sodic'. That means they have a lot of sodium which tends to stop water seeping through the clay, making these soils prone to waterlogging (when the water doesn't drain away quickly). There are also some grey-brown sandy soils up to 80 cm thick. These lie above a layer of clay, too. There are also red-brown clays and gravels in the area. The duplex soils are usually found on the sides of the valleys. Solonetzic soils are usually found on the valley floors. `Solontez' soils contain abundant sodium carbonate (soda) and were laid down under salty conditions, such as a sea floor, and hence tend to be saline.

Figure 3-6: Soils of the Albany region

The soils of the north-eastern part of catchment, south-east of the Stirling Range, are also duplex soils, but with fine, shallow, grey and brown sands up to 35 cm thick. These also lie above clays and blocky clays. (`Blocky' clays form blocks several centimetres square when they dry out.) Duplex soils with deep, sandy features occur on the low hills. Sand dunes and other sandy tracts are near deep, fine, sandy podzols. `Podzols' are soils which are sandy and have been leached of certain minerals, usually containing iron or aluminium. They tend to lie above clay, which does not drain easily. Lakes and swamps in the area have heavy clays and solonetzic soils

The catchment south of the Porongurup Range is made up of gravel and duplex soils about 30 cm deep. The duplex soils are found on the hills and higher areas. The valleys contain gravel duplex soils on the margins with deep sands on the slopes and podzols on the floors.

The soils along the coast are sands (calcareous and siliceous) shaped into parabolic (boomerang shaped) dunes with podsolic soils further inland. There are limestone outcrops near shallow, brown sands. Inland of the coastal sand dunes there are wetlands and swamps made up of podzols and humic podzols (soils with lots of plant matter, called `humus') with some solonetzic, duplex soils and unconsolidated estuarine deposits (such as loose sands and shells).

The granite peaks and ridges in the southern part of the catchment are made up of porphyritic (crystal bearing) granites. These granites are made up of large crystals set amongst much finer grains of rock. The two most common types are called `biotite' (dark mica) and 'adamellite' They are rich in calcium and potassium.

The catchment lies within an area known as the South West Botanical Province which occupies the wetter south-western corner of Western Australia. The vegetation of the area is diverse and complex owing to soil and climatic variations.

The major vegetation communities within the catchment are:

Jarrah, marri and wandoo woodlands occur around Kendenup. There are also low sheoak woodlands and patches of mallee.

Mixed species occur on the summits of the range. Jarrah woodland covers the upper slopes. Jarrah and mallee-heath are found on the lower slopes, while low jarrah woodland is found on the foot slopes. Jarrah and marri woodland mixed with some wandoo can be found in the valleys. Open eucalypt woodland with heath is found on the lower slopes, on the south-eastern side of the range.

Pockets of tall karri trees are found interspersed with occasional jarrah and marri forest and mallee heath. Jarrah and marri woodland are found on the lower slopes. The surrounding plains are covered with banksia and jarrah scrub and mallee heath.

Low jarrah forest mixed with wandoo, yate and mallee heath is found along the upper reaches of the river. This gives way to low jarrah and sheoak woodland with some karri and yate further downstream towards the coast. Jarrah and marri forest is found in the central west of the catchment.

Mixed jarrah and banksia heath with areas of jarrah and karri forest are found on old stabilised dunes. Low peppermint woodland is found in sheltered vales, lying between the sand dunes. Low jarrah, marri and wandoo woodland is found inland, along the southern and eastern shores of Princess Royal Harbour. Paperbark and reed swamps are found along drainage lines, around wetlands and in uncleared areas fringing the harbour.

A band of paperbark and reed swamp lies along the fringes of the harbour's western shore. Paperbark and reed swamps are also found inland along the natural drainage line towards the town site of Elleker. Most of this area has been cleared for grazing and vegetable growing.

About 219 080 ha of the Oyster Harbour catchment (approximately 72% of the total area) and 2950 ha of the Princess Royal Harbour catchment (approximately 35% of the total area) has been cleared. This has mainly been for agricultural purposes on private land. The percentage of private land cleared within the catchments of Oyster Harbour and Princess Royal Harbour is estimated to be 90% and 61% respectively.

A lot of different animals live in the catchment. They are part of a group of animals known as the south-western, or humid-adapted, species. These creatures are adapted to living in wetter climates. In the northern part of the catchment there are also some animals which are adapted to living in semi-arid areas.

Since European settlement, habitats have been destroyed and predators such as cats and foxes have been introduced. This has led to many medium-sized mammals declining in numbers or becoming extinct.

About 29 species of land mammals are in, or next to, the catchment area. These include nine species of dasyurid carnivores (such as the common and fat-tailed dunnarts) which feed on invertebrates. The area is also rich in reptiles. There are eight species of gecko, eight of legless lizard, two species of monitor lizards and 12 species of snake. The numerous wetlands and swamps also support a number of species of frogs.

Bird species abound in the catchment area. These include 240 land, freshwater and marine species. Migratory species, such as waders from Siberia, are found in the estuaries in the southern part of the catchment between September and April each year.

Certain common species live in particular habitats.

| Habitat | Species |

|---|---|

| Jarrah forest: mammals | Western grey kangaroo, western brush wallaby, southern brown bandicoot, bush rat |

| Jarrah forest: reptiles | Dugite, tiger snake, western banjo and moaning frogs |

| Jarrah forest: birds | Emu, silver eye, western rosella, New Holland honeyeater, grey fantail, red wattle bird, tawny frogmouth |

| Karri forest: mammals | Short-beaked echidna, grey-bellied dunnart, yellow-footed antechinus, bush rat |

| Karri forest: reptiles | Tiger snake, western banjo and moaning frogs |

| Karri forest: birds | Purple-crowned lorikeet, western rosella, New Holland honeyeater |

| Wandoo woodland: mammals | Western grey kangaroo, western brush wallaby, short-beaked echidna |

| Wandoo woodland: reptiles | Dugite |

| Wandoo woodland: birds | Emu, brown falcon, nankeen kestrel, western rosella, Port Lincoln parrot, grey fantail, red wattle bird, New Holland honeyeater |

| South Coast: mammals | Western grey kangaroo, southern brown bandicoot, yellow-footed antechinus, bush rat, honey possum |

| South Coast: reptiles | Bardick, dugite, tiger snake, western banjo and moaning frogs |

| South Coast: birds | Whistling kite, nankeen kestrel, Port Lincoln parrot, western rosella, elegant parrot, grey fantail, red wattle bird, New Holland honeyeater, kookaburra |

| Wetlands: birds | White-faced heron, Australian shellduck, Pacific black duck, maned duck, little pied cormorant, black swan, pelican |

| Wetlands: frogs | Western banjo and moaning frogs |

|

Much of the catchment is cleared for agriculture |

There are residential and commercial areas of the town of Albany on the northern shore of Princess Royal Harbour. There are also residential areas at Little Grove on the shores of Princess Royal Harbour, and Lower King, Bayonet Head and Emu Point on the shores of Oyster Harbour.

Further afield from Albany land use is mainly agricultural. In the Princess Royal Harbour catchment, the main kinds of agriculture are market gardening and sheep and beef. Some of the land is irrigated from creeks and drains. A big area in the western section of the catchment is zoned rural. There are areas of irrigated horticultural land. However, a large part of the Princess Royal Harbour catchment is a national park and there are various other recreational reserves in the area.

The main agriculture in the Oyster Harbour catchment is sheep and cattle grazing. Wheat, barley and oats are also grown in the northern areas of the catchment around Mount Barker, including Kendenup and Upper Kalgan. There is also viticulture in the catchment, with a lot of vines grown around Mount Barker and near Albany. This land use is rapidly expanding in the region.